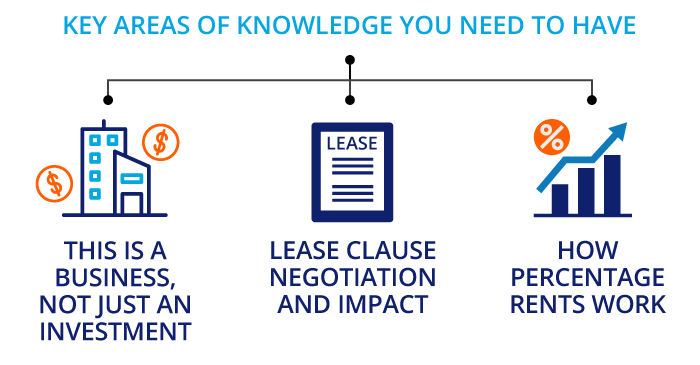

Every Successful Property Manager Knows These 3 Things

Do you think you know enough to be a master-level property manager? Here’s how to step up your game, reduce your risks and actually turn a profit. We have picked the top three areas where you need to have real skills in order to be successful.

1. It’s a business, and you’re in charge

So you bought an investment property. That means you’re an investor now, right? Possibly. Buying a commercial building can be an investment, but buying and leasing a building doesn’t make you a property manager; it just makes you a landlord. Unlike any other major investment vehicles, real estate isn’t a buy-it-and-forget-it venture. Without understanding and following some key business processes, your investment is likely to underperform and could actually lose you a lot of money. Manage your properties poorly and you could end up in court as well.

So what are the keys to being a successful property manager? Let’s dive in!

Understanding financial investments

Most people understand the simple initial financial analysis. Often, investment property shows cover the basics, which are easy to follow. Additionally, there are plenty of free software tools you can download. Typically, the education stops there.

Asset management

Whether you are a building owner or managing someone else’s property, you need to understand building maintenance, basic construction management and capital expenses. Most commercial leases indicate all major capital expenses are the landlord’s responsibility. An unplanned early capital replacement can make your investment returns drop considerably or even lead to losses. Not making timely building repairs can lead to lawsuits from tenants for negligence and preventable losses.

Business structure

Owning a commercial building is a business. Managing a commercial property is also a business. Even though the owner—or a group of owners—may be the same for both, they are often separate businesses, regardless of whether they are owned independently or deal with each other at arm’s length. There is a common misunderstanding among inexperienced owners and property managers that accounting for the property-holding company and the third-party property management company can be merged. It’s important to keep the two separate and maintain organized, traceable financial records.

Accounting

Business success depends on keeping up to date with your accounting and doing it correctly. With commercial net leasing comes a host of accounting requirements specific to allocating costs to tenants according to the terms of the lease agreement. There’s an excellent overview article here and a more in-depth article here to help you better understand these concepts. Your skills and performance in this area determine most of your value as a property manager. Competence in these fields relies on your expertise in asset management, lease administration and well-structured business relationships.

Build your skilled team

Knowing your business is a considerable challenge! To successfully make money on your commercial property investment requires a wealth of industry knowledge. For example, there is building construction knowledge, legal and accounting expertise, real estate market information and connections to keep current. It’s impossible to gain all the required skills in a short period of time. If you want to build wealth and manage well, you need to build your personal network of trusted business connections so that you have reliable experts you can depend on. Just remember that while you can delegate tasks to your team, you are still ultimately responsible for the operation of the business.

2. Lease administration for property managers

Commercial leases are mostly standard boilerplate clauses that rarely affect anything, right? Wrong. They all mean something significant; that’s why they were developed over time and included on most leases. You need to have a grasp of why those clauses are there and what triggers them. The lease terms are there to provide boundaries to acceptable behaviour from the tenant and the landlord. A good lease works like a flow chart, catching various problem conditions and funnelling the outcomes to predictable results. We covered the key points in more detail here.

Understanding commercial leases allows you, the property manager, to be a better negotiator. Lease clauses were developed over the years in response to situations that appeared in disputes and court cases, and from those, a set of semi-standard lease terms were constructed. They use language tested in courts and guided by case law to interpret those specific phrases. Collectively, these are known as “standard boilerplate” clauses. Boilerplate clauses are terms and conditions included in all lease documents to avoid potential legal cases. They also provide a sense of security to the lease parties. They understand they will have reasonably known outcomes if those situations arise. The trouble with the boilerplate is that it was developed—and used—assuming the future will be reasonably similar to the past. That assumption blew up with the pandemic in 2020.

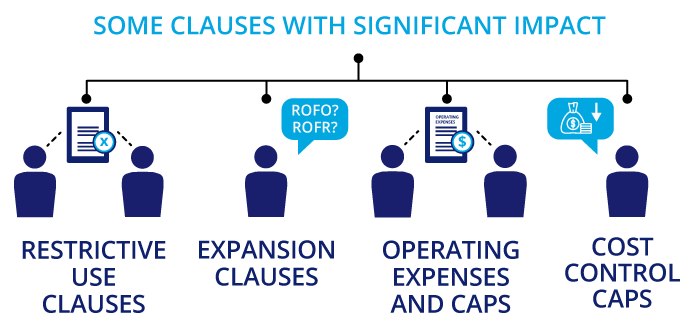

Here are just a few examples of clauses that need serious rethinking:

Restrictive use clauses

These show up in retail leases all the time. Essentially, they prevent one or more parties from engaging in the sale of certain products or services. They are by definition anti-competitive as they restrict the premises from being used for various banned uses. These are often called “radius clauses” because they apply to a circle around the leased premises with a defined radius or even several radii. The closer the infraction, the greater the repercussions for breaking the restriction.

Restrictive use clauses have one of three principal drivers for their inclusion:

- If the tenant signing the lease requests them, they are trying to prevent the landlord from leasing space to one of their competitors. The reasoning behind this is explained by game theory and the Nash equilibrium.

- If the landlord requests it from the tenant, there are at least two reasons. One, they have given exclusive rights to another tenant and need to make all new tenants comply with those previously agreed-to conditions. Two, they could be trying to prevent the tenant from taking its business elsewhere within the same proximity. To make sense of this, you’ll need to understand retail rents (coming up in the next section).

- The last type of restrictive use is where the property manager deems the business use to be undesirable. This type is most evident in shopping malls, for businesses such as gyms and service providers. Once forbidden, they now seem to be the saviours of many commercial retail properties.

Restrictive use clauses can cause headaches for property managers

The problems with restrictive use clauses are many. First, unless the tenant is the first in a cluster of retail locations, other tenants may already have restrictive use clauses enacted or may have the freedom to sell the products the new tenant wants to restrict. Second, the way the lists of products are written is often the issue. What appeared to be clearly defined limits when the lease was written becomes muddied when cross-over products are developed. Are those restricted or not? Third, the remedies stipulated in the lease may be very difficult or expensive to collect. This is especially true when the actual damages cannot be quantified, and the lease provisions seem illegally punitive as a result.

If you want to get into this more, there’s an excellent blog here that digs into this much further. Lastly, restrictive uses embedded in many leases can be difficult to remove as perspectives change on what is considered undesirable.

Expansion clauses

These come in a variety of forms: a Right of First Opportunity (ROFO) or a Right of First Refusal (ROFR). These can be one-time, ongoing or time-limited. They can refer to a specific space or any adjacent or nearby space in the same complex. In all cases, they are for the benefit of a tenant and restrict the landlord’s ability to lease the property.

ROFO

A Right of First Opportunity allows a particular tenant to have the first opportunity to expand into some space that becomes vacant. This is generally preferable to a landlord than the other option, a ROFR.

ROFR

A Right of First Refusal allows a tenant to make a last-minute attempt to match a competing lease offer on available expansion space. The prospective new tenant may find that all its negotiation efforts and costs benefit an existing tenant when this right is exercised. Having a ROFR lowers the interest of new tenants in the landlord’s property.

Problems with expansion clauses

Not understanding the implications of expansion clauses can lead to some tough and very costly situations for a landlord and subsequently for the property manager.

First, make sure the lease uses the correct terms. A ROFR is a lot less desirable to a landlord than a ROFO.

Second, make sure the time limits are clearly defined, both for the right itself and the timeframe a tenant has to exercise it. Is it a one-time right? If the tenant uses it, is it gone or can it be exercised repeatedly any time during the course of the lease term when any new space becomes vacant? Can it still be used later for another opportunity if it is refused once?

Third, what happens when more than one tenant has an expansion right over the same space? With ongoing rights, previously spaced tenants may become adjacent to the same open premises.

Finally, what constitutes a matching offer? Tenants are not identical, and a landlord may prefer one type of business over another. Additionally, the property manager may project that a lease with one tenant will be more lucrative, which—all else being equal—makes that offer better than lease rates alone describe.

Operating expenses and caps

We’ve seen all kinds of additional rent capping clauses. Most of them aren’t written well enough to be worth the paper they were written on.

The lease sections on operating costs are often one of the longer ones, but they almost invariably rely on two definitions that aren’t really definitions at all. They split property expenses into “operating costs” and “capital expenses” as if these words have no gray area between them. To an accountant, once these amounts are recorded in the journal, they are either one or the other. But in practice, property managers often see operating and maintenance costs where tenants see capital repairs.

Using two accounting words doesn’t make the definition any clearer to anyone. The best clauses include:

- A schedule that lists specific details about equipment and asset classes

- The type of maintenance or replacement

- Whether it is deemed an operating expense or a capital expense

- Who is responsible for having the maintenance done

- Who pays for it

- How it is paid for

- The amortization period

At least then you have a hope of both parties having the same understanding of cost allocations.

Cost control caps

Precisely because the additional rent is such a practical mess in most leases, lawyers and negotiation teams look to simply cap those operating costs by putting an artificial limit on what the landlord can recover from that tenant. Let’s take a look at the various solutions we have encountered and the problems with each.

The straight-line cap

This is the simplest cap. It can have a variety of forms, from fixed amount annual increases to incremental percentage increases. The laziest implementation is what is known as the “base year” for additional rent. In this case, the net lease specifies a monthly rent, which includes the first year of the additional rent. Base year leases rarely get a proper reconciliation. Likewise, the amount for the base year additional rent is seldom specified in the lease. Moreover, the straight-line method fails to account for times when there are significant maintenance upgrades to the property, such as repainting or regenerating the landscaping plan. It either leads to the property manager missing out on additional rent recoveries or the more likely scenario where the property never gets any significant updates.

Year-over-year versus initial rates

Some leases cap the increases based on the previous year and some base the cap on the initial year. The year-over-year method penalizes the landlord every time they successfully bring in a lower budget, as they are forced to reset the cap lower for the next year. The initial rate method constrains the increases below a line that cannot be exceeded. This results in a fairer cap towards the landlord. Most often, the problem encountered is that the initial rate is rarely included in the lease document, making this cap impossible to enforce.

Controllable expenses

In an effort to negotiate an impasse over the additional rent cap, a common compromise is to insert the words “controllable expenses” into the cap clause language. While this sounds like reasonable language, applying it in practice is anything but. We can likely agree that the property taxes are out of the scope of the landlord’s control. What about property insurance? Winter maintenance costs or liability insurance? In one exercise, about 3% of additional rent was actually discretionary to the landlord. The rest was out of their jurisdiction or controlled by market forces that the landlord couldn’t influence.

Using controllable expenses can lead to complicated accounting procedures. Each of the expenses will need to be classified, applicable caps set and, for each expense class, the initial rate or amount must be recorded. It’s seldom worth the effort. For example, it could cost $1,500 of billable time to calculate a $300 annual savings on the tenant’s additional rent.

3. Understand percentage rents

Every property manager should understand how percentage rents work. Percentage rents are a complex rent calculation method for determining the rent based on a fixed minimum rent and a variable portion based on the tenant’s monthly sales. A percentage rent is rent applied above a minimum base rent and is a percentage of the gross sales that the tenant makes from the premises. The percentage is often estimated and reconciled on a monthly or annual basis and may be averaged over a period of time.

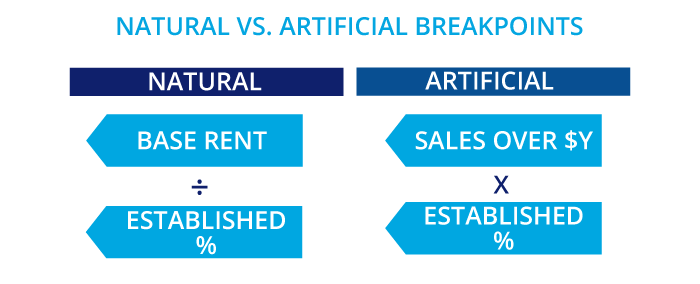

Breakpoints

The percentage rent applies once gross sales meet a certain threshold. The point at which percentage rent is paid is called a “breakpoint” and can either be a natural or artificial breakpoint. If the breakpoint is never met, the tenant is only obligated to pay the minimum rent.

An artificial breakpoint is simply a dollar amount of sales, where a specified percentage of gross sales above an agreed-upon dollar amount is to be paid in percentage rent. For example, if the percentage rent is 25% of gross sales above $25,000 a month, then the percentage rent on $30,000 gross sales is $1,250.

To calculate the natural breakpoint, simply divide the base rent by the established percentage. The logic behind the natural breakpoint is that a retailer should only pay the percentage rent on sales over and above what is required to pay the minimum rent.

Purpose of the percentage rent

The purpose of percentage rent is to tie the tenant’s success to the amount of rent it pays and, therefore, to the landlord’s success. From the tenant’s perspective, it functions as insurance against hard times, lowering the rent it must pay if sales go down. From the landlord’s perspective, if the tenant does well, the landlord can cash in on that success too.

Pitfalls of percentage rents

While percentage rents seem to benefit both the tenant and landlord, there are some risks associated with this method.

Online shopping

The most common issue in recent times has been the definition of which type of sales constitute the basis of the percentage rent calculation. Do online sales count? What about online sales that are picked up in-store? How should product returns be handled? What if the item was purchased online, picked up in one store but returned to a different store? Online sales could potentially have much lower margins for the retailer than in-store-only items. The possible scenarios get out of hand very quickly. And the rapid nature of change online makes predicting and accounting for changes years into the future impossible to record adequately in a lease document.

Property valuations

Lenders use property valuations for mortgage limits based on the cash flows for the property. Rental rates that allow for monthly variability will result in lower valuation for the property. This is particularly true if there is currently an economic downturn. Property owners may find there is less financing available to them for properties with percentage rent leases.

Cash flows

With percentage rents, the rental rates lower immediately on slower sales instead of in the next leasing cycle. Pandemic-related closures resulted in immediate loss of cash flows for retail property owners. Using a simpler method of fixed rent increases provides greater certainty.

Increased accounting work

Tracking each tenant’s sales, returns and losses for each rent period for multiple categories of goods is a time-consuming process. A portion of the rent paid in advance and a portion paid retroactively further complicates the monthly rent reporting. Receiving the sales information from the tenant in a timely manner can be another problem. As well, the landlord may need access to confidential information if an audit of the tenant’s sales figures is necessary. Unless they are large tenants with sales numbers to justify the additional accounting work, it’s best to use a simpler method. That is the primary reason that percentage rents have nearly disappeared from common use.

The bottom line

When working as a property manager, remember you are in an ongoing business relationship with your tenants. Your success in business depends on the success of your tenants. The property owner’s success depends on the ability to manage the properties (whether privately owned or financed). The owner only receives a return on their investment if the properties are profitable. More than ever, we are all in this together.

Be reasonable

There’s an old adage that says, “When you go to court, only the lawyers win.” Therefore, it is in your own best interest to be reasonable in your business deals. Seek to foster an atmosphere of cooperation with your tenants. In fact, you are on the same side of the table when you face the property owner. It’s often not worth the time to track and calculate arbitrary limits when spending time clarifying the underlying concerns is the far better solution.

Be flexible

If the pandemic taught us anything, it is that the past performance doesn’t predict the future. Avoid unnecessarily encumbering either party for low probability events, questionable gains or because “we always have those clauses in every lease.” Don’t try to capture every low probability scenario. Instead, work out the major issues and put a resolution mechanism in place for dealing with the unforeseen ones. This is especially relevant for smaller landlords and tenants where legal costs will quickly make combative approaches unprofitable.

Be transparent

The best way to deal with uncertainty is to be able to trust your business partners. Trust requires clarity and transparency. CRESSblue Commercial Property Management software is specifically designed to accurately record transactions, automatically break down costs and be transparent to tenants and owners alike with audit trail reporting on every transaction. The easiest way for a property manager to achieve their goals is by using CRESSblue Commercial Property Management.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended as professional advice; please consult a competent professional for advice specific to you. This blog is written to stimulate thinking on concepts related to commercial leasing. Please join the discussion with your experiences.

Martin Sommer, CEO, CRESS Inc.

Martin is a founder and the CEO of CRESS Inc., a Canadian SaaS company that automates lease administration and asset management. Martin also manages Karanda Properties Limited industrial portfolio as Director of Operations in all areas of commercial property management, including new development, asset management, capital expenditures, operations, leasing and lease administration of the industrial portfolio. Martin writes about property management workflow and issues. Book Martin to speak at your industry event.